NOTES FROM KREUZBERG/THE PAST (1980): TO PEE IN THE DEVA’S SHOES

A Deva is an angelic creature, a higher life-form, which surrounds us with its light and supportively accompanies us. In India there’s one on every corner, cordially close at hand of beady-eyed models of virtue on pincushions.

You can find those creatures of light in Germany, too, though you have to look closely, at least in Berlin, at least today.

In the Berlin of the late 70s, however, they were considerably easier to find: back then a Deva was often simply a long- and greasy-haired young man, originally perhaps a Wolfgang or Roland, just back from India, where he had searched for his essence, ferreted it out, and judged it to be rather cool. A fact that now, after his return, had to be announced through an extravagant name.

To eliminate possible resistance of fellow human beings to his encircling, luminous orb, Wolfgang-Roland, the Deva, began in a preschool co-op. Namely, ours. Perhaps he assumed that we children, who he took to be very much like angels, would recognize him in his gleaming radiance and be overwhelmed with light and love. After that, he probably thought he could work on the mothers, and then, perhaps, on the whole world.

He could never have known that in the briefest amount of time those children would recognize him in terms not so much angelic as asinine, and would then overwhelm him with something quite other than light. A judgement only somewhat ameliorated by a smaller average body height.

We at the Kangaroo preschool defended and marked our territory with fervor. This territory consisted of a 70-square-meter accomodation on grey, dusty Urbanstraße in Berlin’s Kreuzberg district, where there were hardly any trees and not much daylight–and in which, therefore, the seasons tended to reveal themselves through the varying intensity of dog-poop smells.

Behind our space there was a small yard with a garden, fully outfitted with monkey bars and a rat poison-scattering hag, who wanted to see us all dead. It was perfect, we needed nothing else. And as for angels, we had one of those too. Her name was Birgit.

Birgit was as round and sweet as an apple, and for us she was, at the age of seventeen, the embodiment of motherliness and general meekness. When I recently met her again on the street after almost thirty years, with a horde of snot-nosed, insolent Kreuzberg grubs in tow, she looked exactly as I remembered her. Just a bit less round, but that could be because she was never especially fat and the only photo of her I’ve saved is from Carnival season, when she was dressed as the Very Hungry Caterpillar.

Birgit was so perfect for us that we would accept no angels aside from her. Even Christine, her short-term colleague with the jaunty haircut, whose standoffish manner betrayed no particularly angelic ambitions, had a tough go of it. But Christine, unlike the Deva, was only clipped. Not in the shoe, not in the foot, but certainly in the heart. In our field-trip photos from the Spreewald she looks, with her flaring nostrils and wrinkled nose, as if she’s trying to catch a whiff of something all the way back in Kreuzberg. You don’t know whether that look comes from disgust for her demoralizing task–hustling ten bratty children through the woods–or homesickness for poop-smeared Urbanstraße.

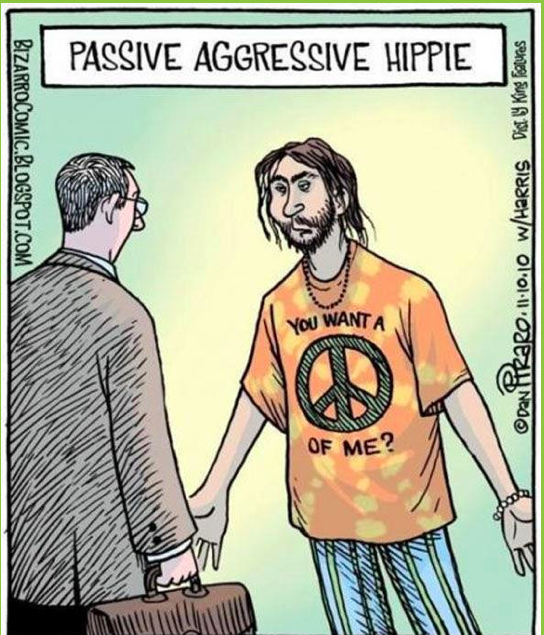

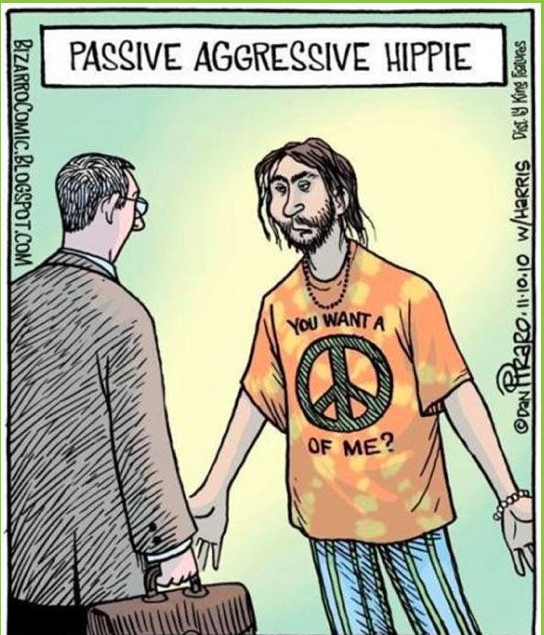

The Deva, who naturally was called not Deva, but rather “The Deva,” was a pain in the ass from day one. He spoke softly and gently when he should have raged and bellowed; he congratulated himself for finding good in us, rather than simply finding good in us; he retreated into himself, when we wanted him to retreat out the door and never come back.

Over the first few weeks we tried to make that happen with the few weapons that we, in our brief lives, had learned to control: “Why? Why?”, “You’re dumb, haha!”, or biting. Janne and Sebastian took charge of the biting–finally we saw the payoff of all the hours of practice they had put in on the climbing rope, locked together in a snarling tangle. With pleasure and great precision they promptly sank their teeth into the calves of the Enlightened One, who then broke into a kind of folk-dance, but unfortunately did not disappear into thin air.

The “You’re dumb, haha”-faction consisted of rather guarded, bashful children, who could really cut loose here. Although the more courageous of them augmented their technique with pokes, they could not provoke the arrogant Roland into a name change.

As for me, I joined the “Why? Why?”-group. But I soon realized that even this rather subtle tactic of attrition would yield nothing from our Deva.

It could be–though my memory here is cloudy–that I marginally had something to do with the next escalation of nastiness.

We soon prepared ourselves (the “You’re dumb, haha”-faction was elected) to distract the Deva with poking. Then a group of Daredevils, which consisted of certain members of the “Biting”- and the “Why? Why?”-groups, set out for the teachers’ cloakroom, snuck by the parents (who, as they were sitting cross-legged and smoking in the kitchen, debated whether we children might have been right to call the Deva a self-aggrandizing sack of shit), and peed in the Deva’s shoes.

He left us with soggy shoes, a fading plume of light tucked behind him, and was seen no more.